Standalone Executables

Learn how to package your Lua apps for distribution to end-users

Introduction

Since Lua is an interpreted scripting language, it doesn't allow distributing binary releases on its own. However, there's a workaround:

Instead of compiling Lua files to binary objects, you can simply distribute the scripts as text files (or bytecode objects). However: Since end-users likely won't have a Lua interpreter available, you must ship one alongside the application's script files. This is the approach that Evo takes, but the scripts are bundled into a ZIP archive and embedded into the executable you distribute to the user's system.

The interpreter can then detect the presence of a ZIP archive inside its own executable and read data from it as needed. To run your application, the interpreter will extract the files at runtime and load them "behind the scenes", invisible to the user. The concept may seem a bit strange, but it works because ZIP files can also be executables. It's similar to Java's JAR files or the Windows installers of old.

This page describes the options that Evo supports out of the box for creating these executable ZIP files, and limitations to the approach.

Building Standalone Apps

There's only two steps needed to create a standalone executable:

- Prepare a directory that contains only the files to be distributed in a ZIP archive

- Run

evo buildin this directory (or provide the path to it as an additional argument)

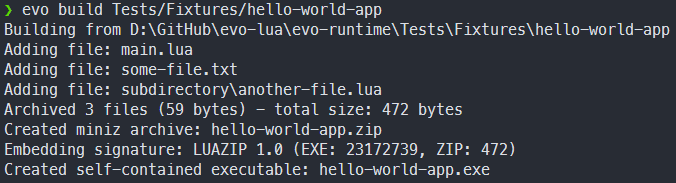

You should see a summary with some technical details about the executable that was built:

After the process has completed, you will notice the presence of two build artifacts:

- The standalone executable itself (here called

hello-world-app.exe), which end-users should be able to run on their system - A ZIP archive that contains all the bundled files (here called

hello-world-app.zip) - look inside to see what you would ship

The executable is all you need to distribute; it includes the ZIP archive alongside the Evo runtime used to build it (and a signature).

Loading Bundled Files

You'll need to create a "loader" called main.lua, which initializes the rest of your application. Place it in the directory that you package. Evo will extract the entry point, main.lua, and run it when it detects a self-contained app. Your entry point can require modules from within the virtual file system just like any other file:

-- main.lua

local someModule = require("someModule")

dump(someModule)

local someOtherModule = require("subdirectory.someOtherModule")

dump(someOtherModule)

In the above example, Evo will load both files from the VFS, if they exist, or use the default require behavior otherwise:

- Whenever a module exists in the VFS and on disk, the VFS takes priority (for security and performance reasons)

- All

.(dots) in the path names are internally replaced by/to cleanly map to the VFS paths

This change isn't disruptive; all Evo does is add a custom searcher that looks into the VFS first when it dectects it is running a standalone executable. You can still add your own searchers to load different versions, or remove them.

The path resolution follows all the standard rules. It can be configured with package.cpath and LUA_PATH.

Lua C-API Modules

Because this mechanism makes use of Lua's require system, you can only load Lua C modules with it. In order to do so, you should bundle your application with a compatible version of the C module and use it like you would any other module available on the user's system. The vfs.searcher will discover it and let Lua handle the rest.

The path resolution follows all the standard rules. It can be configured with package.cpath and LUA_CPATH.

Although many Lua C modules are available and can be used with require, this has a significant impact on performance and often incurs additional maintenance costs. Using the C API is of course supported, but not the recommended approach to loading native libraries in this runtime. If you do want to use them, you must make sure they're built for LuaJIT, which is based on Lua 5.1 and not compatible with more recent C API versions.

There's another way to get access to C code that you want to ship with your application, described below.

Shared Libraries and the FFI

Evo allows you to use shared libraries (.dll, .so, .dylib files) using LuaJIT's foreign function interface. This introduces potentially unsafe code paths, but has significant performance benefits. It's also a lot easier to create FFI bindings; no glue code is needed beyond the definitions for types and function signatures (called "cdefs").

The vfs library supports loading these kinds of modules even from within self-contained app bundles:

local ffi = require("ffi")

local uv = require("uv")

local vfs = require("vfs")

-- When run from a LUAZIP app, the cache is already populated with the current app itself

-- Otherwise, you can use vfs.decode to load the app bundle here - but it'll be much slower

local zipApp = vfs.cachedAppBundles[uv.exepath()]

-- For brevity's sake, export only one function. This could easily cover the entire library interface

local cdefs = [[

const char* zlibVersion(void);

]]

ffi.cdef(cdefs)

-- Loading may fail for various reasons, so that vfs.dlopen returns a failure tuple (nil, errorMessage)

-- Given the right paths, this will work when running the script from disk and also when bundled later

local sharedLibraryPath = "zlib.so" -- ... or .dll, .dylib (platform-specific)

local zlibShared = vfs.dlopen(zipApp, sharedLibraryPath) or ffi.load(sharedLibraryPath)

-- If loading did succeed, all of the previously defined functions can now be used from Lua

local versionString = ffi.string(zlibShared.zlibVersion())

printf("Successfully loaded zlib version %s from the LUAZIP bundle!", versionString)

There is no path resolution or magic search prefixes to configure. The vfs.dlopen searcher simply browses the executable's archive for a file with the given path, which is relative to the root directory. It then extracts the shared object file and uses ffi.load, which will invoke the operating system's facilities for loading shared libraries.

You can use vfs.dlname to get some portability, which is used by default when no file extension was detected.

To see what's inside the archive, use the miniz or vfs libraries. The system is designed to be transparent.

Native Look and Feel

You may want to perform cosmetic surgery to provide a better user experience, such as setting an app icon or hiding the console window. Evo currently doesn't provide any tools to help with this part of the process, though it's something to consider for the future.

Since icons are always platform-specific, you'll need to use third-party tools (e.g., wine has some for Windows, or Apple's icon utilities).

Limitations

The nature of interpreted languages puts some limits on what you can do. The following might help you decide if this works for you.

Binary Size

If you're shipping a full Lua runtime alongside your application, this will clearly increase the total binary size of the artifacts you have to distribute. While Lua interpreters are generally tiny, as a full-fledged runtime environment Evo is a bit bulkier, and you'll be effectively adding all of the contained libraries regardless of whether you actually use them. Especially for small programs this could be significant.

The good news is that it's not that big compared to other options, and also you could ship a leaner, trimmed-down version of Evo.

Obfuscation

While this provides very limited security against tampering or reverse engineering efforts, publishing Lua code (or even bytecode) very clearly makes it relatively easy to access a more readable version of the source code. This generally won't be an issue for open source projects, and even many proprietary applications (as few users would bother to read the source code even if you waved it in their face).

For commercial use cases, however, you may want to consider moving business-critical parts into a native DLL/SO file and ship that.

Runtime Dependencies

Although Evo comes with quite a few "batteries" that you don't need to manually distribute, the builtin APIs don't cover every use case.

Complex programs often require the help of advanced libraries, which are usually bundled alongside the app (as DLL or shared object files). While LuaJIT can easily access these, you will still need to include them. Scripts inside a standalone executable still need to load libraries at runtime. This is what other interpreted languages do, as well.

Unfortunately, shipping binaries to different Linux systems may be troublesome. But at least users there won't necessarily expect it. You can call ffi.load with just the library name and rely on system libraries installed by the user, which works on any modern distribution with a built-in package manager (such as apt or pacman).

Both the libraries and the runtime executable included in a self-contained application bundle must be compatible with the architecture of the system that's ultimately meant to run them. Cross-compilation is not supported.

Licensing Issues

Because you're providing a complete runtime (including lots of third-party code) alongside the program, certain licensing terms must be adhered to. In the case of Lua, LuaJIT, and indeed all of Evo this should however be unproblematic. All of them use permissive open-source licenses that should play nice, but it's best to conduct a proper legal review to ensure compliance won't cause any problems.

For open-source projects, there obviously won't be any issues. But it's still good practice to review your dependencies and their licenses.

Alternatives

If the above limitations are making the "combined ZIP executable" approach untenable, you could consider some other options:

- Using an installer (such as MSI or DMG) to distribute files to the end user would give you more fine-grained control

- Compiling a binary "addon" (DLL/SO) and loading it with LuaJIT's foreign function interface can be a viable alternative

- Writing the application in a compiled language altogether and distributing binary artifacts only would be the last resort